In high-stakes projects—especially in public-sector programs, infrastructure initiatives, and mission-critical IT systems—recurring quality issues are more than operational annoyances. They are signals of underlying problems that, if ignored, can erode performance, inflate costs, and compromise stakeholder confidence.

One of the simplest and most effective tools I’ve used to address these issues is the 5 Whys technique: a structured method for getting beyond symptoms to uncover the true cause of a problem.

What the 5 Whys Method Is

The 5 Whys is exactly what it sounds like: ask “Why?” repeatedly—usually around five times—to drill down from a visible symptom to its root cause.

It was originally developed by Sakichi Toyoda for the Toyota Production System, but the method has since been adopted widely across industries, including government, defense, and large-scale program management.

The value lies in its simplicity: no specialized software, no statistical modeling—just disciplined inquiry and logical thinking.

Why It Works in Project Quality Management

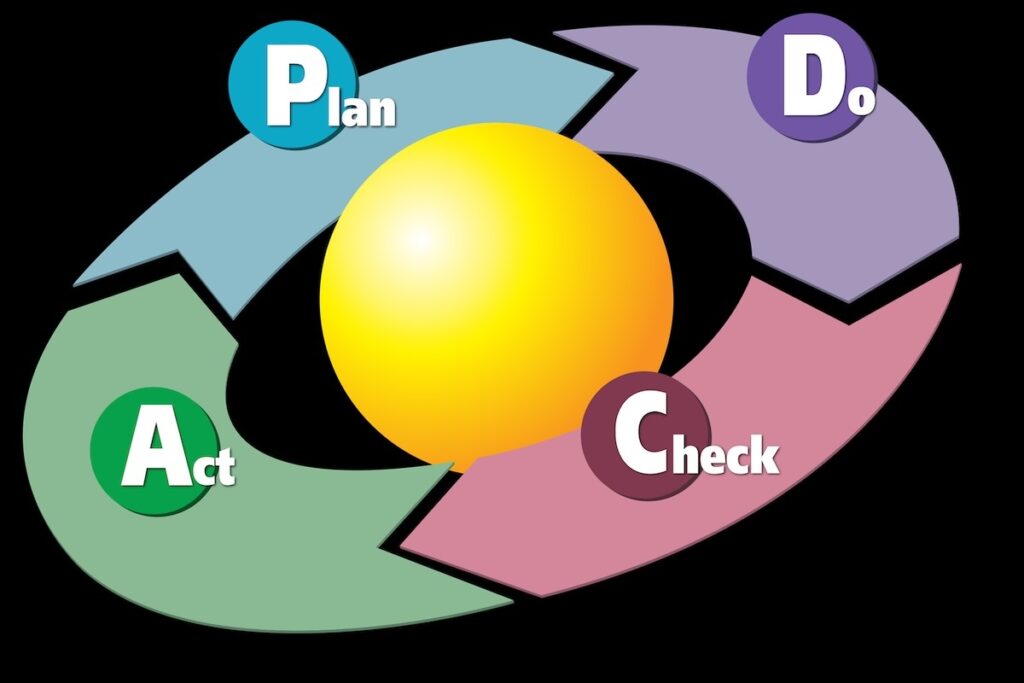

In the PMBoK context, the 5 Whys fits naturally within Control Quality and Manage Quality processes.

Its benefits include:

- Clarity – Avoids jumping to conclusions or applying cosmetic fixes.

- Speed – Can be done in a matter of minutes with the right people in the room.

- Collaboration – Brings cross-functional perspectives to the problem.

- Prevention – Addresses the cause, not just the symptom, reducing recurrence.

Real-World Example 1: Data Validation Delays

In a multi-agency government data integration project, user acceptance testing was delayed repeatedly due to incorrect data in test environments.

Applying the 5 Whys:

- Why was the data incorrect? – Test datasets were missing key fields.

- Why were key fields missing? – The export scripts didn’t include all required fields.

- Why didn’t the export scripts include them? – They were based on outdated data schemas.

- Why were the schemas outdated? – Schema updates were not communicated to the test environment team.

- Why weren’t they communicated? – There was no formal change notification process between the production and test data teams.

Root cause: Lack of a change notification process.

Permanent fix: Implemented a formal data schema change control procedure. The delays stopped.

Real-World Example 2: Emergency Response System Downtime

A public safety communication system experienced intermittent downtime during extreme weather events.

Applying the 5 Whys:

- Why was the system down? – Power supply units failed.

- Why did the power supply units fail? – They overheated.

- Why did they overheat? – Cooling fans stopped functioning.

- Why did the fans stop functioning? – Filters were clogged with dust.

- Why were the filters clogged? – Maintenance intervals were too long for environmental conditions in certain regions.

Root cause: Maintenance schedule not adapted to local environmental conditions.

Permanent fix: Adjusted maintenance frequency by region; no further weather-related outages occurred.

Best Practices for Using the 5 Whys in Projects

- Assemble the Right Team – Include people with direct knowledge of the process or system in question.

- Define the Problem Clearly – Agree on the exact symptom before starting.

- Stay Objective – Avoid assigning blame; focus on facts.

- Validate Each “Why” – Ensure each answer is evidence-based, not speculative.

- Act on the Root Cause – Implement corrective measures and track their effectiveness.

Integrating the 5 Whys into Your Quality Plan

- Add it as a standard step in your Root Cause Analysis procedures.

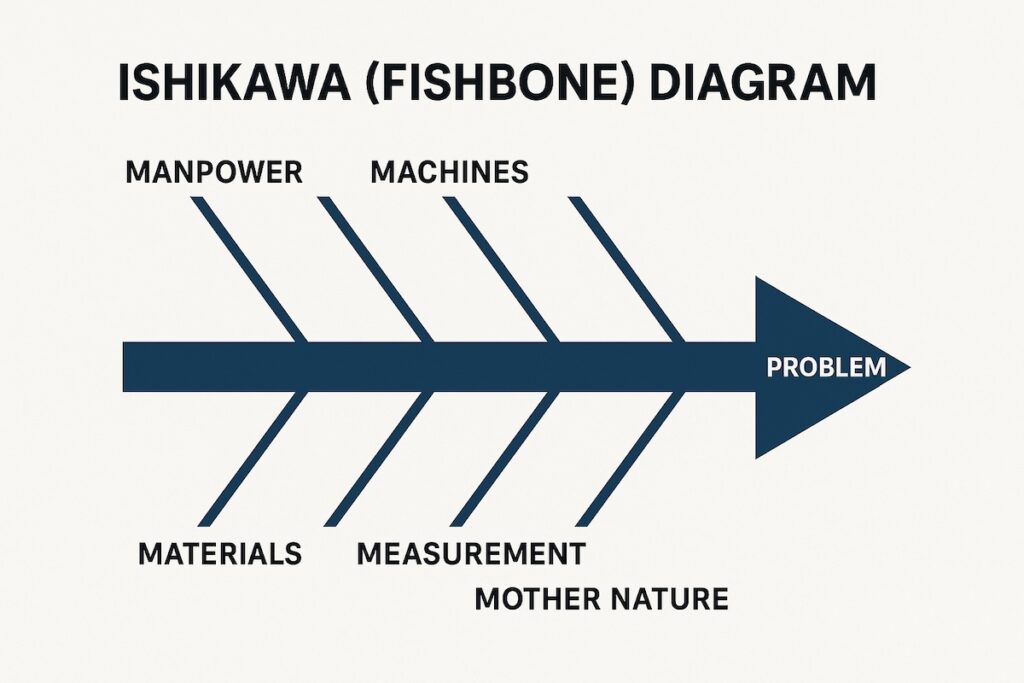

- Use it alongside other tools, such as the Ishikawa Diagram, for complex problems with multiple potential causes.

- Document findings in your lessons learned repository to prevent recurrence in future projects.

Closing Perspective

In complex, high-visibility projects, the difference between a recurring quality issue and a one-time defect often comes down to whether you addressed the real cause.

The 5 Whys is a deceptively simple tool that—when used with discipline—can uncover the systemic gaps that traditional inspections miss. And in mission-critical work, eliminating those gaps is not just good practice—it’s essential for operational integrity and public trust.